本期经济学人杂志关于“亚洲四小龙”的【特别报道】中的第一篇题为《After half a century of success, the Asian tigers must reinvent themselves》的文章论述了在经过半个世纪的发展,“亚洲四小龙”——中国香港、中国台湾、新加坡和韩国必须再次自我变革,从迷恋经济增速的“发展型社会”转变为增速友好的“福利型社会”。

20 世纪 60 年代早期到 20 世纪 90 年代,“亚洲四小龙”通常都有两位数的经济增速,但亚洲金融危机后,中国逐渐成为新的发展明星。今年美国的经济增速要比“四小龙”中的任何一个都要快。“四小龙”存在一些长期难以解决的问题,比如台湾工资增长停滞,韩国经济被大企业把控等。目前它们还要解决一些和西方国家一样的难题,如缓解不平等、提高生产率、应对老龄化以及在中美关系中保持平衡等。

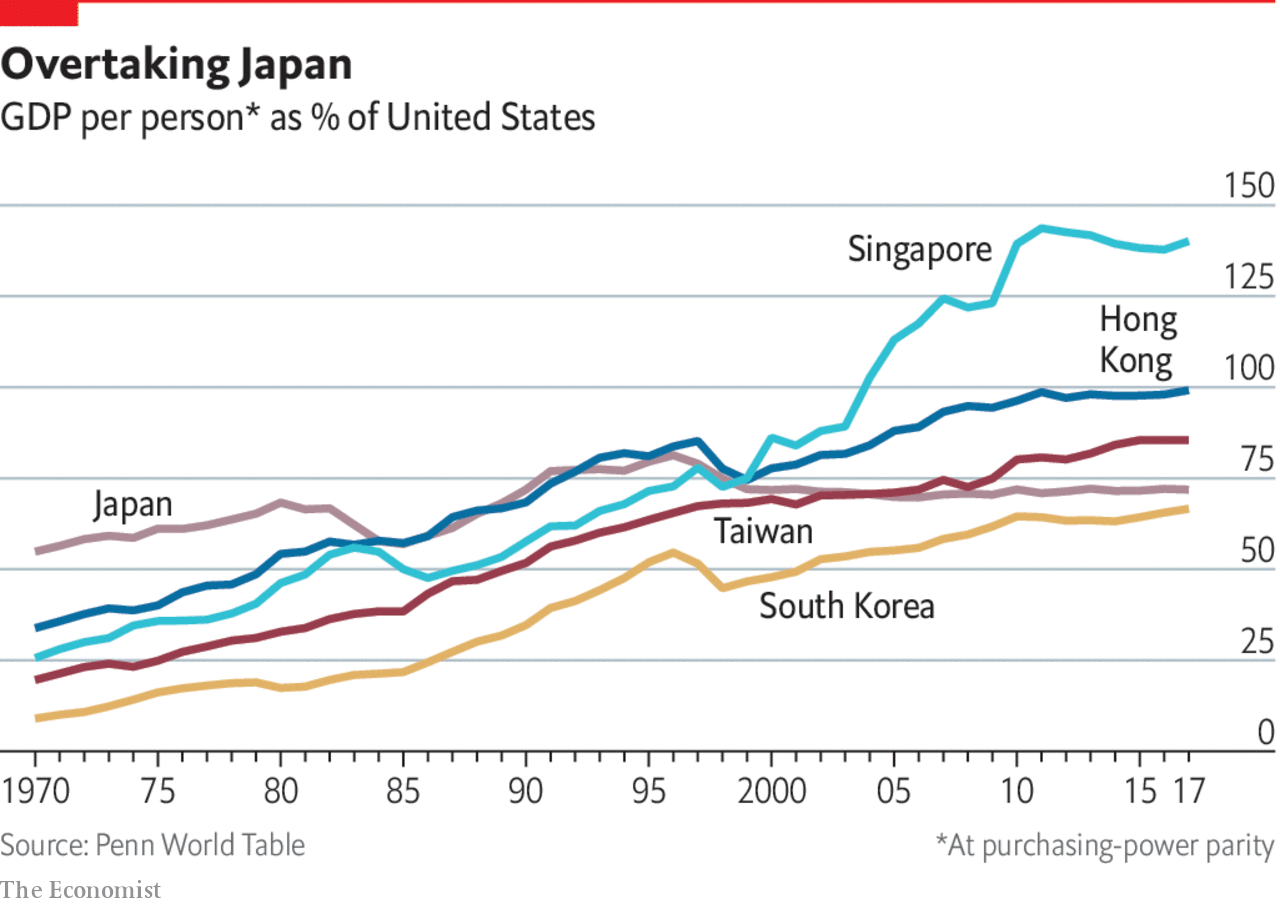

但这些问题并没有完全拖垮“四小龙”,按照购买力平价 (PPP) 计算的人均 GDP 仍非常高,韩国将成为第四个超过日本的“四小龙”成员。它们也在很久之前成功跨过了所谓的“中等收入陷阱”。

这份特别报道旨在重新审视“四小龙”经济变化的本质,并由此得出了四个大的论点:

- 一、“亚洲四小龙”面临的问题源于经济成功,而非失败;

- 二、有人认为中国台湾、韩国喧闹的政治阻碍了经济发展,但文章认为中国香港所谓的不充分民主也带来了不满和不信任;

- 三、福利不足也可能阻碍社会和经济的发展,“四小龙”必须从迷恋经济增速的“发展型社会”转变为增速友好的“福利型社会”;

- 四、“四小龙”对世界其他地区来说像经济晴雨表一样重要。

After half a century of success, the Asian tigers must reinvent themselves

SPECIAL REPORT: ASIAN TIGERS

Asian tigers

After half a century of success, the Asian tigers must reinvent themselves

They must move from growth-obsessed developmental states, to growth-friendly welfare states, say Simon Rabinovitch and Simon Cox

Print edition | Special report

Dec 5th 2019

The four Asian tigers—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan—once fascinated the economic world. From the early 1960s until the 1990s, they regularly achieved double-digit growth. A generation that had toiled as farmers and labourers watched their grandchildren become some of the most educated people on the planet. The tigers started by making cotton shirts, plastic flowers and black wigs. Before long, they were producing memory chips, laptops and equity derivatives. In the process they also spawned a boisterous academic debate about the source of their success. Some attributed it to the anvil of government direction; others to the furnace of competitive markets.

Then the world turned away. The Asian financial crisis destroyed their mystique. China became the new development star, even if, to a certain extent, it followed their lead. The tigers themselves seemed to lose their stride. This year America is on track to grow more quickly than all four of them.

They all have seemingly intractable problems: stagnant wages in Taiwan, the dominance of big business in South Korea, an underclass of cheap imported workers in Singapore and, most explosive, a government in Hong Kong that will not, or cannot, listen to its people.

But it is a mistake to write off the tigers. A closer look at their economic record shows that, contrary to the gloom that sometimes pervades them, they have much to boast about. The trajectory of their gdp per person, calculated at purchasing-power parity, has remained impressive (see chart). They blew past the supposed middle-income trap long ago. And South Korea will soon become the fourth tiger to overtake Japan, its former imperial ruler and economic mentor.

They have also gained ground on America. Singapore passed it in the 1990s; Hong Kong drew level in 2013; and the other two have narrowed the gap. Indeed, in the past five years (2013-18), the gdp per person of Singapore and Hong Kong has grown faster than every country above them in the income rankings. With a couple of exceptions, the same is true of Taiwan and South Korea.

In their economic maturity, the tigers merit renewed attention. They face many of the same issues that bedevil the West: how to mitigate inequality; how to gin up productivity; how to cope with ageing; and how to strike a balance between America and China. They do not have all the answers, but they do have novel, albeit sometimes foolish, approaches that are in themselves instructive.

Little dragons

This special report will examine the changing nature of the tigers’ economies and make four big claims. The first is that many of the tigers’ problems result from economic success, not failure. They have defended their global export share for years, despite steady increases in labour and land costs. Now, though, they will struggle to expand their exports faster than global demand itself. They have also reached the technological frontier in many industries. That makes further improvement harder: they are no longer catching up with global best practices but trying to reinvent them.

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father, once claimed that harmony and stability are chief among “Asian values”. The tigers still cherish these things (who doesn’t?), but many of their citizens see fairness as a precondition for both. That observation leads to this report’s second big claim: when a sophisticated citizenry aspires to democracy, frustrating that aspiration can be imprudent as well as unjust. Some argue that the blustery politics of Taiwan and South Korea—complete with high-profile corruption cases, parliamentary fisticuffs and fiercely partisan media—have hindered their growth. But a proper examination of the tigers’ record does not support that argument. Instead, what has become clear in Hong Kong is that a lack of democracy is a grave liability, sowing dissatisfaction and mistrust.

Third, the tigers’ thin welfare states have also become a hindrance. Their leaders have traditionally worried that redistribution and social spending would sap their populations’ motivation to work. But social insecurity instead risks sapping their populations’ willingness to embrace technological change. As the tigers’ populations get older, their governments also face more pressure to spend on pensions and health care. And they need to alleviate the economic burdens that dissuade young people from having children. The tigers’ growth-obsessed “developmental states” must, in short, become growth-friendly welfare states.

Finally, the tigers are important as economic bellwethers for the rest of the world. They are unusually exposed to deep global cycles: in technology, finance and geopolitics. The manufacturing tigers have dominated narrow slices of the technological supply chain, focusing on techniques and chips that are vital for high-speed 5g telecoms networks and “big-data” processing. Hong Kong and Singapore, meanwhile, have positioned themselves as financial bridges between China and the world, making them highly sensitive both to China’s success and its stumbles. And all four of the tigers depend on the maintenance of geopolitical calm as America, the incumbent superpower, adjusts to a new rival.

These cycles can be difficult to manage—even in an upswing. Booms in finance and technology can concentrate wealth in a few hands, such as South Korea’s chaebol chipmakers or Hong Kong’s property tycoons. On the downside, the threats are even greater. Twice in the past quarter-century the tigers have been rocked by financial crises. The long boom in demand for semiconductors in smartphones and computers has recently turned, hurting South Korea and Taiwan. But it is the geopolitical challenge that most worries them now: a “new cold war” between China and America would shake the foundations of the tigers’ prosperity and security.

Methodologically, this special report begs an obvious question. Does it make sense to lump the tigers together? Two are cities; the others decent-sized countries (Taiwan’s population exceeds 20m; South Korea’s 50m). Two are sovereign members of the United Nations; one is a territory of China; the other exists in a diplomatic netherworld. Taiwan and South Korea are fierce democracies; Hong Kong and Singapore trust their electorates less. Two still rely on manufacturing; two are now high-end service providers.

Yet for all these differences, there is much they have in common. They are among the world’s most open trading economies, with all the volatility that implies. They have nonetheless maintained high rates of employment and thrift, even as their living standards have improved. They are, to varying degrees, caught between China and America. And all four are faced with complex social problems that stem from their remarkable growth over the past half-century. The four tigers have achieved prosperity without complacency, wealth without repose. Their efforts to remain in front are not guaranteed to be successful. But they are guaranteed to be fascinating. ■

This article appeared in the Special report section of the print edition under the headline"Still hunting"