本期经济学人杂志【商业】板块下这篇题为《LVMH tests the limits of luxury》的文章关注的是法国奢侈品品牌 Louis Vuitton 的母公司路易威登集团 (LVMH) 于 25 日宣布,以约 162 亿美元收购美国精品珠宝商蒂芙尼 (Tiffany & Co) 的并购案。文章认为该交易将巩固路易威登集团在奢侈品行业的龙头地位,同时也将面临一些后续挑战。

此次收购将是路易威登 CEO Bernard Arnault 执掌公司 30 年来最高金额的收购交易,超越 2017 年以 70 亿美元获得 Christian Dior 控制权的交易规模,创下奢侈品行业最大并购纪录。

奢侈品业具有高固定成本的特点,比如市场营销、商铺租金等。像 LVMH 这样的大集团可以发挥规模优势,在租用新的商铺时有更强的议价能力、更好的广告效果,并且旗下各品牌可以共享花大代价建立的网上商城。此外,分析师认为品牌在大企业内可以做得更好,比如 2011 年被 LVMH 收购的一家意大利珠宝商 Bulgari 在整合后利润上升了五倍。类似地,LVMH 将会给予 Tiffany 充分的时间和资金帮助,翻新店铺并推向高端市场。

文章同时认为奢侈品业的大企业也面临诸如供应、如何处理好旗下这么多不同业务等问题。贝恩咨询发布的报告显示,2018 年全球个人奢侈品消费总额预计将增长 7% 至 2810 亿欧元,主要得益于中国市场和年轻消费者的贡献。2000 年中国的贡献很小,但现在中国贡献了全球个人奢侈品 1/3 的销售额。

文章认为 LVMH 也面临一些挑战,比如不确定的未来,中国带来的增长不可能一直持续;如何吸引千禧一代的年轻人;以及如何使用好社交媒体,做好线上销售。Mr Arnault 今年 70 岁了,他的接班人是否拥有他那样的才能管理好公司值得关注。时代不停变化,商业模式与时代紧密相连的奢侈品业该如何应对?

LVMH tests the limits of luxury

The everything-that-shines store

LVMH tests the limits of luxury

Can the conglomerate of bling grow any larger?

WHAT DO YOU buy the luxury group that has everything? More diamonds, apparently. On November 25th LVMH, already the biggest beast in global luxury, announced it was taking over Tiffany & Co, where Wall Street bond traders sink a few bucks to improve their chances of turning girlfriends into fiancées. The American marque will become the 76th maison of the Parisian group, joining Louis Vuitton, Dior and Veuve Clicquot champagne. How many more can fit under the corporate umbrella of Bernard Arnault, LVMH’s boss and biggest shareholder?

The deal is as richly priced as a flawless gem. LVMH will pay $16.9bn including net debt, equivalent to nearly four years’ sales at Tiffany. Nonetheless, the takeover was greeted with the enthusiasm befitting a suitable engagement. Luxury, once little more than a cottage industry dominated by family firms in Europe, has become the preserve of a few giant conglomerates. In recent decades there has been a sense of inevitability when another well-known company has fallen into the clutches of LVMH or its rivals, Kering (home of Gucci and Balenciaga among others) and Richemont (which owns Cartier and Montblanc).

The acquisition cements the place of LVMH at the peak of the luxury world. Its rise has been nothing short of dazzling since Mr Arnault took it over three decades ago. Its shares have risen threefold in the past five years, including a 60% run since January. Worth around €206bn ($227bn), LVMH now vies with Royal Dutch Shell as the most valuable firm based in the EU.

Mr Arnault, whose family owns nearly half of LVMH (and a solid majority of voting rights), is said to be Europe’s richest man. From the gritty town of Roubaix in northern France, he turned a family construction firm to property, then luxury. He snapped up Dior as part of a package of distressed textile assets in the 1980s, then seized control at LVMH. The “wolf in cashmere” has all the trappings of a $100bn fortune, from a public art collection housed in a Parisian museum designed by Frank Gehry to his impeccably tailored Christian Dior suits and a couple of newspapers.

“LVMH dominates a structurally favoured sector, buoyed by globalisation and income inequality,” says Luca Solca of Bernstein, a research firm. Its success is the result of being the right size—big—in the right business at the right time.

Start with the industry. Sales of luxury goods, such as handbags, posh watches and Hermès scarves, have grown by about 6% a year since 1996 according to Bain, a consultancy. It estimates the industry will be worth €281bn this year. Chinese shoppers, who barely featured in 2000 but now account for a third of all sales, have added much of the fizz.

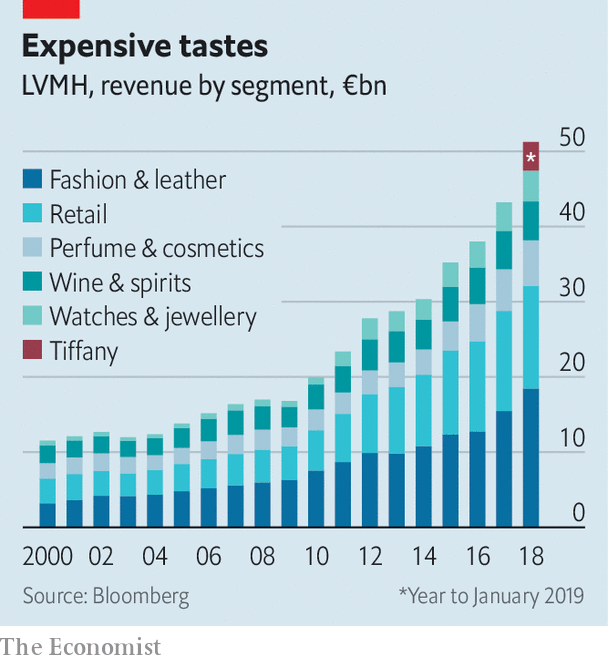

Size has brought more rewards. In an industry with high fixed costs—spent on marketing, but also on eye-watering rents for shops on flashy thoroughfares—selling more translates into better margins. LVMH has achieved nearly double the industry’s growth rate in the past two decades, and last year sold over €46bn-worth of extravagance (see chart). That is more than three times the figure for Kering and Richemont, its nearest rivals.

Mr Arnault emerged as the most obvious buyer for Tiffany in part because scale begets advantages not available to smaller bauble-peddlers. That might seem odd at first. Compared with lesser industries, mergers in the luxury world kick up few opportunities for cost-cutting or synergies. Nobody expects Tiffany watches to be sold in Louis Vuitton stores, for example.

But analysts think brands can do better within a conglomerate. Take Tiffany. Its shareholders had pestered management to improve margins and raise sales fast, unduly hurrying its turnaround efforts. LVMH says it will give Tiffany time and money, for example to renovate stores and push upmarket. It did something similar with Bulgari, an Italian jeweller. Mr Arnault this week said profits there had risen five-fold since LVMH took it over in 2011. The group does not disclose how each brand is doing (its annual report contains more pictures of jewel-laden models than financial minutiae), easing the pressure on creative types to meet quarterly targets.

Scale has more mundane advantages, too. Conglomerates have more clout when negotiating, for example, with landlords of new malls in China. They can browbeat magazines for better advertising rates. Hefty costs associated with building e-commerce sites can be shared.

Such advantages suggest more consolidation. But there are limits for LVMH and others. One is supply. The timeless brands that conglomerates crave by definition need a long history, and these are relatively few. Those that remain independent, such as Chanel or Rolex, preserve that status fiercely. Mr Arnault has got round this by subtly expanding the scope of luxury, for example by branching out into hotels.

Another limit, which is particular to LVMH, is whether any group can handle so many different businesses. In other industries, conglomerates are regarded as unwieldy and have fallen out of fashion. Kering slimmed down by spinning off Puma, a sportswear brand, last year. So far the mood is for building empires, not dismantling them. Some wonder if Richemont and Kering might merge to boost their prospects.

LVMH is not without challenges. The luxury sector’s future is uncertain. Growth in China will not last for ever, especially if trade tensions continue. Even Dom Pérignon drinkers feel the impact of recessions. Marketing has had to evolve to attract millennials who care about Instagram and sustainability. More shopping is happening online, where mastodons like Amazon and Alibaba lurk.

Perhaps half the firm’s profits come from a single brand, Louis Vuitton. Mr Arnault has made it clear that LVMH is a family firm and that one of his children (four of whom work in the business) will take over. At 70, he remains firmly in charge. But as time passes, the question of whether his heirs have inherited his talent for flogging objects of desire will come into focus.

And can luxury continue to sell to ever more people yet retain its cachet? So far it has. But the industry Mr Arnault helped create is young, despite the timeless quality it seeks to exude. It has thrived by spending extravagantly to get people to buy beautiful foreign things they do not need. It is the archetypal business model of the times. But what if times change?■

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline"The everything-that-shines store"

Print edition | Business

Nov 30th 2019