本期经济学人杂志【经济金融】板块这篇题为《Part-time jobs help women stay in paid work》的文章主要以西欧女性为例探讨了兼职(非全日制)这种工作方式对女性的影响,一方面兼职能让女性获得收入的同时兼顾家庭,另一方面相比全职兼职不利于女性的职业发展。

荷兰有 3/4 的参与工作的女性做的是兼职工作,这个比例是全球最高的。20 世纪中叶,服务业的兴起让女性能更多地参加工作,兼职能让女性同时兼顾家庭与工作,享受生活,但西欧的女性对 GDP 的贡献率只有 33%,这主要是因为她们的工作时长较少。

除了日本韩国(女性被排除在高薪工作外),兼职对全球各国女性的不利影响主要有以下三个原因: 一、 兼职的小时工资低于全职;二、兼职得到的工作更有可能是一份“坏工作”,缺少培训和法律规定的正当权利;三、兼职可能是个陷阱,让大多数女性实际兼职的时间要比原先打算的久,甚至有些人一辈子再也没有做过全职工作。

文章还提到,一些研究结果显示相比女性一个想照顾家庭的男性很难获得兼职机会,所以在很长时间里,许多家庭只能继续牺牲女性的职业发展机会,让女性做兼职工作,男性做全职工作。

Part-time jobs help women stay in paid work

Balancing act

Part-time jobs help women stay in paid work

But they can also stop women’s careers from progressing

Print edition | Finance and economics

Sep 5th 2019| AMSTERDAM

Getting hold of a Dutch woman on a Wednesday can be tricky. For most primary schools it is a half-day, and as three-quarters of working women are part-time, it is a popular day to take off. The Dutch are world champions at part-time work and are often lauded for their healthy work-life balance and happy children. But these come at a price. Among western European countries, the Netherlands has the largest gap between men’s and women’s pension entitlements, and the largest in monthly income. Even though a similar share of Dutch women are in the labour force as elsewhere in western Europe, their contribution to gdp, at 33%, is far lower, largely because they work fewer hours.

In the rich world part-time working took off in the second half of the 20th century, as services replaced manufacturing and women piled into the labour market. It remains essential to helping women work, particularly after giving birth, and in countries with traditional gender norms. But it can prolong—or even worsen—gender inequality and make women less independent by locking them into jobs with worse pay and prospects. Differences in working hours explain a growing part of the gender pay gap. That share could increase as labour markets disproportionately reward those willing and able to work all hours—who are mostly men.

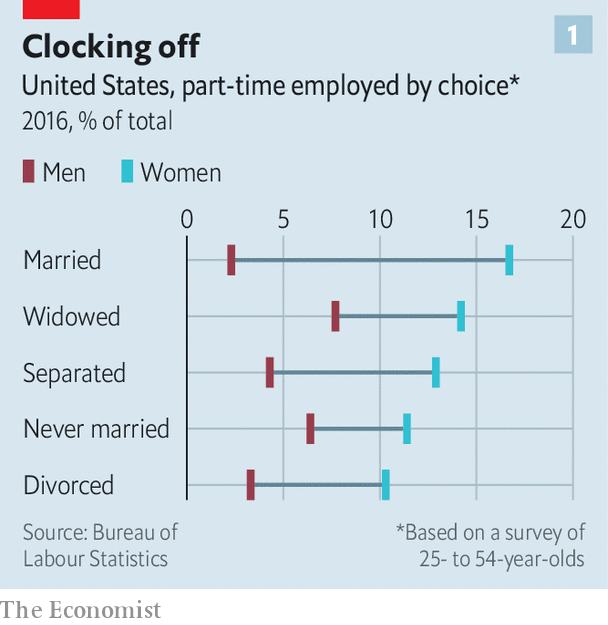

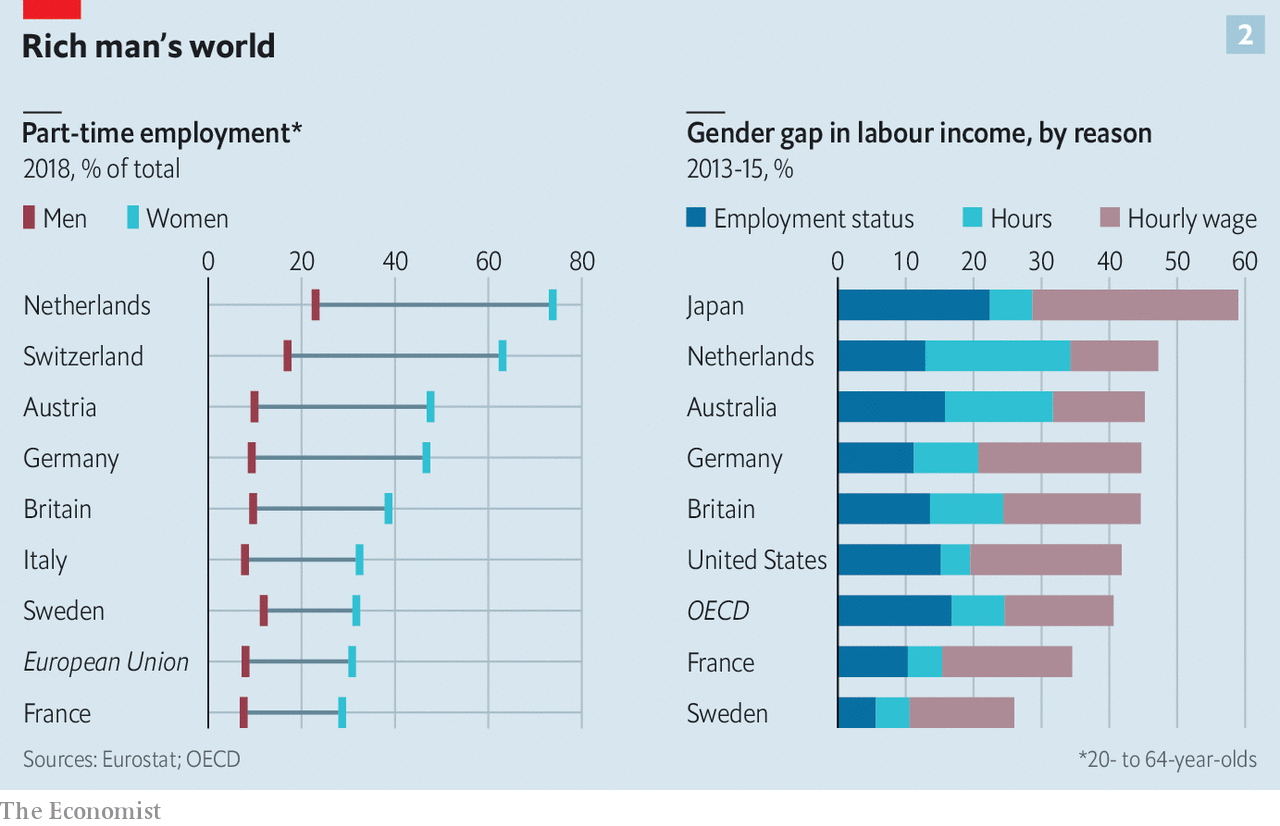

Almost one in five workers globally are part-time (defined as working fewer than 35 hours a week). In many countries married women are the group most likely to work part-time, and married men the least likely to (see chart 1). In the eu nearly one in three women in work aged 20-64 are part-time, compared with fewer than one in 12 men (see chart 2). After the financial crisis the number of “involuntary” part-timers—workers who would take more hours if they could get them—rose alarmingly in some countries, including America, Britain and Spain.

Family obligations often lead women to choose to work part-time. In America 34% of female part-timers, and just 9% of male ones, cite this as their main reason. In the eu the figures are 44% and 16%. “Part-time work can be very positive when the alternative would have been women leaving the labour market altogether,” says Andrea Bassanini of the oecd. Its availability has been credited with the rapid growth of female participation not just in the Netherlands, but also in Germany, Japan and Spain, where it has shifted the standard household from one to one-and-a-half breadwinners. In Germany all the growth of the female workforce in the past 15 years has been down to the rise in part-timers.

But for women, there is a cost. Within the oecd—apart from in Japan and South Korea, where women are excluded from most well-paid jobs—part-time working and the gender pay gap are significantly correlated. The mix of reasons varies from country to country, but three stand out.

First, in nearly everywhere that has data available, part-time jobs pay less per hour than full-time ones. Sometimes this is within an occupation. A recruitment firm, Indeed, found that the hourly-pay penalty for part-timers in America was highest in jobs that rewarded strong client relationships, such as in retail, or where workers are always on-call, such as web development. But more often it is between occupations: the types of jobs that can readily be done part-time, or are offered part-time, are lower-paid than those that are not.

Second, part-timers are more likely to have a “bad job”—one that offers little training and few legal rights. In America 39% of female part-time workers, compared with 6% of full-time men and 9% of full-time women, are in the “secondary” labour market, with low pay, no benefits and few opportunities to move to better jobs, writes Arne Kalleberg of the University of North Carolina in “Precarious Work”. According to Patricia Gallego-Granados of diw, a think-tank in Berlin, going part-time in Germany often involves “occupational downgrading”: accepting a job that does not use the worker’s skills to the full.

Even good jobs can become worse when done part-time. A study of American women in elite occupations who voluntarily moved to part-time “retention” positions created for them found that they were put on a “mummy track” with less chance to progress. In Britain, says the ifs, a think-tank, wage increases stop when a woman moves to a part-time role. For graduates the penalty is particularly large, since they earn a larger return on experience. The ifs calculates that a quarter of Britain’s hourly gender pay gap can be explained by women’s greater propensity to work part-time.

Third, part-time work can be a trap. Although often a short-term expedient, most women who start to work part-time continue for longer than intended. Many never go full-time again. The share of Dutch women working full-time peaks at age 25-30 and then falls, never to recover—quite unlike the pattern for men, who peak later and then stabilise. A study in Australia found that the likelihood of a woman changing hours, contract or employer fell by 25-35% after she became a mother. “The best kind of part-time work is for a short duration,” says Jon Messenger of the International Labour Organisation.

For an employer, the benefit of part-time rather than full-time workers depends on the sector. When demand varies a lot, part-timers bring large productivity gains, according to an extensive study of employees in pharmacies. Companies where full-time employees work more than 48 hours a week could benefit from more part-timers, since productivity falls off above that threshold. But otherwise the evidence is mixed. In countries with fewer protections for part-timers (the Netherlands and Norway are rare exceptions), companies choose them for that reason.

Indeed, the gender pay gap could even widen further. One reason is growing demand for “flexible” workers, by which employers generally mean the opposite of what workers with caring responsibilities mean: permanently on-call rather than with predictable, mutually agreed hours and the ability to work from home. “I wouldn’t be surprised if this new demand for flexibility creates new types of biases against women,” says Mr Bassanini. Related to this is the rise of jobs with extremely short hours, mostly done by women.

Meanwhile the hourly reward for working in professions where very long hours are the norm, such as law and consulting, has risen dramatically. A study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that America’s gender pay gap would be as much as 46% smaller were it not for the increasingly disproportionate rewards for working extra hours since the 1980s. It estimates that average wages rise by 20% in an occupation for every 10% rise in average hours. This premium for uncompromising jobs means “women have been swimming upstream in terms of achieving wage parity,” write the authors. To make matters worse, says Youngjoo Cha of Indiana University, women in households where the man works more than 60 hours a week are three times as likely to stop work as women in households where the man works 35-50 hours a week. (A wife working long hours does not make a man any more likely to quit.)

As long as some people work punishing hours, the prospect of closing the gender pay gap appears remote. Men in the rich world are twice as likely as women to work more than 48 hours a week. In America 20% of American fathers, but just 6% of mothers, work more than 50 hours a week. This is one of several arguments made by campaigners for a four-day working week.

Yet even modern, family-oriented men face a dilemma. Their requests to work part-time are more likely than women’s to be rejected. And those who do work part-time risk discrimination. A study in which cvs were sent to prospective employers found that men whose cvs showed them as working part-time were just half as likely to get a call-back as those who were identical, except that they were working full-time. Part-time women faced no such discrimination. As long as such double standards exist, many couples will still choose to scale back her career, rather than his.■

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline"Balancing act"

Print edition | Finance and economics

Sep 5th 2019| AMSTERDAM

The Economist print edition covers