本期经济学人杂志【商业】板块熊彼特专栏文章的标题为《Hard times for SoftBank》。

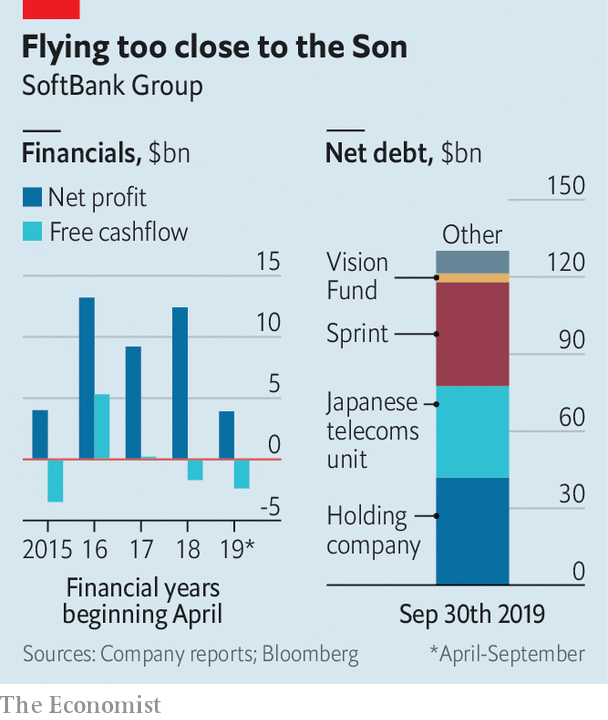

11 月 6 日在救助 WeWork 后日本电信和科技巨头软银宣布了 60 亿美元的损失。成立于 1981 年的软银因为 2000 年投资了阿里巴巴,拥有阿里巴巴 24% 的股份,此外它也控制了美国的 Sprint 和英国的 Arm 等电信和科技类公司,还成立了远景基金来进行大规模产业投资。但在多年投资扩张后,软银的已成为全球第五大负债最严重的非金融企业,负债高达 $1660 亿(扣除现金后的净额为 $1290 亿)。

文章认为目前的软银有三点让人感到担忧: 第一、要保证有足够多的收入来支付高昂的利息、分红以及费用;第二、不幸的是软银所投资的一些有名的企业的潜在表现不是很理想,甚至出现了亏损;第三、所投资的企业和基金背负着沉重的债务。

文章后半部分提到软银董事长孙正义应当适当减少对公司的控制,变得 soft 一点,毕竟那么大的公司他不可能面面俱到且总是作出正确的判断。

注一: 远景基金筹集的资金中,很大部分是债务融资,这些以优先债形式存在的资金意味着作为基金管理人的软银每年需要向债权人们支付高达几十亿美元的利息。The Vision Fund has $40bn of debt-like securities with a hefty coupon.

Hard times for SoftBank

Schumpeter

Hard times for SoftBank

After the WeWork fiasco Masayoshi Son’s empire needs a rethink

Print edition | Business

Nov 7th 2019

Companies and financial vehicles that get into trouble often have common characteristics: high debts, accounting that is hard to understand, opaque assets that are hard to value and managers who have a hard time facing reality. That more or less fits the description of SoftBank, a giant Japanese telecoms and technology conglomerate founded and run by Masayoshi Son, which on November 6th announced a $6bn loss after bailing out WeWork, a loss-making property firm. Speaking in Tokyo, Mr Son put on a defiant display and insisted that SoftBank has a valuable portfolio of tech assets that the outside world does not appreciate. But soon enough, like most troubled businesses, SoftBank will have to confront its underlying weakness: a lack of cashflow to back up all of the hype. It may have to shrink and could end up being broken up.

Mr Son has cultivated an eccentric persona by making dramatic predictions about how technology will change the world and insisting his firm will last 300 years. But SoftBank is no curiosity. After a long expansion binge it is the world’s fifth-most-indebted non-financial firm, with gross consolidated debts of $166bn (after deducting cash the net figure is $129bn). These are owed to banks and investors around the world and to Japanese households. SoftBank controls important companies, including Sprint, an American telecoms outfit, and Arm, a British tech firm that is a vital cog in the semiconductor industry. Saudi Arabia has invested a pile of public money in Mr Son’s tech-investment arm, known as the Vision Fund. This vehicle has gone on an acquisition spree, buying stakes in tech “unicorns”, several of which, including WeWork and Uber, a ride-hailing pioneer, have struggled of late.

SoftBank is hard to understand because it is complex and because Mr Son’s explanation of its purpose often changes. It was founded in 1981 as a software distributor. In 2000 Mr Son was clever (or lucky) enough to invest in Alibaba, which became China’s most valuable company. Today SoftBank owns 24% of the e-commerce giant. Between 2006 and 2015 SoftBank morphed into a telecoms firm, buying first Vodafone’s Japanese arm and then Sprint. The most recent phase started in 2016, when Mr Son pivoted again, this time to investing in fashionable tech firms, and created the Vision Fund. The vehicle raises money from outside investors but is run by SoftBank and enters into various transactions with it.

The results of all this can be baffling. Is SoftBank a conglomerate or a venture-capital firm? Does Mr Son act in the interests of SoftBank’s shareholders or the Vision Fund’s investors? Analysts have struggled to find a coherent way to think about the firm, in one case, optimistically, describing it as tech’s Berkshire Hathaway. Shareholders have been lukewarm; SoftBank’s share price has gone nowhere for half a decade. Credit-rating agencies have been tolerant. Never mind that SoftBank’s consolidated accounts—which, roughly, tally the figures for all the assets that it controls—show it has burned up a cumulative $2bn in free cashflow over the past five years (see chart), even as it has booked a gargantuan $43bn of profits.

The simplest way to view SoftBank is as an indebted holding company that owns a basket of assets, which are of mixed quality and often themselves indebted. These include Arm and stakes in Alibaba, the Vision Fund, Sprint and a Japanese telecoms operator. Mr Son argues that this holding company is financially strong. It is legally responsible for only a subset of the group’s net debt—some $41bn—with the rest owed by operating companies that could, in principle, default without bringing the whole house down. Meanwhile, the value of the stakes that the holding company owns are worth several times its debts, at $247bn. Half of this sits in Alibaba. In other words, if you liquidated everything, the holding company could easily pay off its obligations. What’s not to like?

It is a seductive story, with three big flaws. First, the holding company still needs to receive enough income to pay its interest bills, in the form of dividends and fees paid to it by the firms and funds that it invests in. At the moment it does but the margin for error is tight. That feeds into the second worry, that the underlying performance of the firms that SoftBank invests in is weak, suggesting that their valuations may fall. WeWork has got lots of attention for its vast losses. But consider Arm, supposedly a jewel in the crown, which SoftBank bought for $31bn in 2016. In the most recent quarter its sales fell year-on-year and it made a loss—hardly a stellar performance.

The third worry is that firms and funds that SoftBank invests in have too much debt. The Vision Fund has $40bn of debt-like securities with a hefty coupon. Even if SoftBank is not legally liable it may feel it has to bail out entities that it sponsors. This has just happened at WeWork, into which SoftBank has pumped another $6.5bn. Worries over borrowing levels are compounded by reports that SoftBank and Mr Son have put in place unusual debt structures. For example, SoftBank is reported to have loaned money to employees to invest in the Vision Fund. Mr Son himself is reported to have taken out personal loans secured against his 22% stake in SoftBank. Corporate structures that depend on layers upon layers of debt are inherently fragile. When they come under pressure the end result is often hard to predict.

Mr Son’s instinct is to expand by launching a second $100bn-plus Vision Fund, from which SoftBank could presumably earn fees and to which it could perhaps sell assets, while remaining in control. But the WeWork fiasco raises profound doubts about his judgment and SoftBank’s valuation process.

From soft to soggy

Instead, the obvious path for SoftBank is a dose of austerity. That would mean stemming the losses at the tech firms owned by the Vision Fund and selling down more assets; SoftBank is already trying to merge Sprint with T-Mobile, a rival. It would also require Mr Son to cede control. His vision of SoftBank involves one man being largely responsible for hundreds of billions of dollars—and for juggling no small number of competing objectives and interest groups. If you think that approach still makes sense you have to be soft in the head.