本期经济学人杂志在【经济金融】板块这篇题为《Soaring pork prices hog headlines and sow discontent in China》的文章中讨论了这一年来主要由”非洲猪瘟“导致的“飞起”的中国猪价,以及因为猪肉在中国人的饮食中的较高地位,所以对通胀率和央行货币政策有较大影响。

经济学家很少考虑猪的平均怀孕周期 (115 天),或者猪仔出栏要多久 (6 个月),但在中国了解母猪哺乳周期等基本知识是他们工作的一部分。猪肉是中国人餐桌上的重要菜肴,因此猪价涨跌不仅影响通胀还会影响人们的生活。最新数据 (注一) 显示,8 月中国猪肉价格环比上涨 23%,创月环比增长最高记录,同比来看猪价上涨 47%。

以前猪价上涨农民会很快出产更多生猪,但这次情况不一样,“非洲猪瘟”使得能繁母猪 (注二) 大量减少。中国央行最近降准 50 个基点刺激经济,猪肉驱动的通胀可能会限制其进一步降息降准的空间。

中国人一年要消费 5,500 万吨的猪肉,相当于世界猪肉消费的一半。胡春华副总理 8 月指出今年的猪肉供应缺口将达 1,000 万吨,这一数字高于世界猪肉市场所交易的猪肉量。政府已经开始向市场释放冷冻肉储备,这一储备建立于 20 世纪 80 年代,来应对类似目前猪肉供应紧张的情况。

随着猪肉价格飞涨,现在吃牛肉和鱼肉的人也开始多起来。分析师认为猪肉在中国 CPI 中的比重已由许多年前的 3% 降到了目前的 2% 多一点。在过去一些年里,为了推动银行系统去杠杆中国的货币供应增长相对缓慢,工业品价格已经跌进通缩,因而中国央行倾向于 write off (抵消?) “非洲猪瘟”带来的供给冲击影响。但风险是高企的猪价可能蔓延都其他食物上,对工资施加不必要的上涨压力。

文章最后认为一切都会慢慢好起来,中国会逐渐发展规模更大、管理更好的生猪养殖场,猪周期带来的冲击会越来越小,猪肉将不再作为通胀指示器。China’s pigs would once more be braised by chefs rather than appraised by economists.

注一: 这里的数据应该来自国家统计局公布的《2019 年 8 月份 CPI 和 PPI 数据》

注二: 能繁母猪、仔猪、外二元母猪和猪周期等可以搜一两篇券商研报阅读。

全球各国猪肉消费量排名

Soaring pork prices hog headlines and sow discontent in China

A porcine phenomenon

Soaring pork prices hog headlines and sow discontent in China

The government dips into its pork reserves to quell both grumbles and inflation

Print edition | Finance and economics

Sep 12th 2019| SHANGHAI

Economists rarely think about the average gestation period of pigs (115 days) or the length of time a sow needs to reach sexual maturity (roughly six months). But in China, a basic knowledge of hog-breeding cycles is part of the job. Pigs are so central to the Chinese diet that the ups and downs of pork prices have an outsized impact on inflation. Once again, porcine expertise is in demand: African swine fever has devastated China’s pigs, complicating its economic outlook.

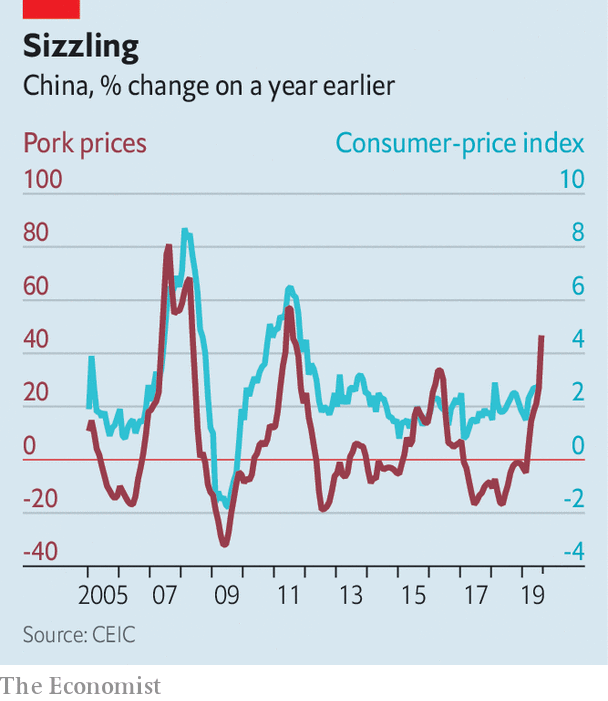

New data show that pork prices leapt by 23% in August from July, the highest monthly jump on record. On an annual basis they were up by 47%. The feed-through to broader inflation has been modest so far. But pork is certain to become more costly in the coming months, pushing consumer prices up further (see chart).

In the past, when pork prices soared farmers quickly produced more pigs. That is harder now because the population of breeding sows has collapsed. The central bank has started to ease monetary policy as growth weakens, but the spectre of pork-led inflation, even temporary, could limit its space for cutting interest rates.

China consumes 55m tonnes of pork annually, as much as the rest of the world combined. Hu Chunhua, a vice-premier, said in August that the supply shortfall this year will be about 10m tonnes, more than is traded on international markets. The government has announced subsidies and low-interest loans to encourage pig farmers to expand. But since at least a third of China’s hog herd has been wiped out, these measures will not generate instant results.

Several cities have started offering limited amounts of discount pork. Others are giving cash to low-income residents. China has also started to release meat from its frozen-pork reserves—created in the 1970s for just such emergencies. But they cover barely a tenth of the shortfall. On September 10th Life Times, a Communist Party-managed newspaper, had an unusual banner headline: “Pork, it’s better for you to eat less”. It dressed up its article as healthy-eating advice, but readers surmised that it was trying to put lipstick on a very pricey pig.

Yet the government’s big concern for now is affordability, not inflation. Pork, together with rice, has long been close to a daily necessity in China. The word “meat” by itself almost always refers to pork. But during the past decade pork has diminished in importance, as a share of both dinners and overall spending. Beef and fish have grown in popularity. Middle-class urbanites, not to mention the wealthy, are spending their money on much else besides. Analysts now reckon that pork is little more than 2% of China’s consumer-price index, down from 3% a few years ago.

Moreover, it takes more than pork for inflation to be a problem. In 2008 and 2011, inflationary spikes followed big increases in the money supply; price rises, though pronounced for pork, were a much broader phenomenon. Over the past couple of years the money supply has grown much more slowly as regulators have pushed banks to reduce their leverage. Prices of industrial goods have fallen into deflationary territory. The central bank will thus be inclined to write off African swine fever as a supply shock. The risk is that sky-high pork prices spread to other food items, placing unwanted upward pressure on wages.

In the meantime people are adjusting. Liu Zhiqiang, a retired factory worker in Beijing, used to treat his family to pork ribs once a week. “Now I just toss some pork shavings into fried dishes and have more eggs instead,” he says. Xishaoye, a restaurant chain popular for pork-filled crispy buns, said that it was researching whether it could use chicken as an alternative.

All going well, China will eventually emerge from this mess with bigger, better-managed pig farms. The hog cycle would become less volatile, and pork cease to matter as an inflation indicator. China’s pigs would once more be braised by chefs rather than appraised by economists. ■

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline"A porcine phenomenon"