本期经济学人杂志【经济金融】板块下这篇题为《Why the unemployed in America could face a lost decade》的文章关注的是新冠疫情对美国劳动力市场带来巨大打击,失业人口不断增加。文章认为,如果未来经济不出现奇迹性反弹,美国就业市场可能再次面临“失去的十年”。

受疫情影响,迪士尼宣布旗下酒店和主题公园中的十万名员工将开始休假,Uber 也将裁撤 1/5 的员工。今年 3 月开始,共有 2,600 万美国人申请了失业保险。截至 4 月 18 日,美国劳动力市场参与者中有 10% 的人接受了失业金,这一比例创历史新高。

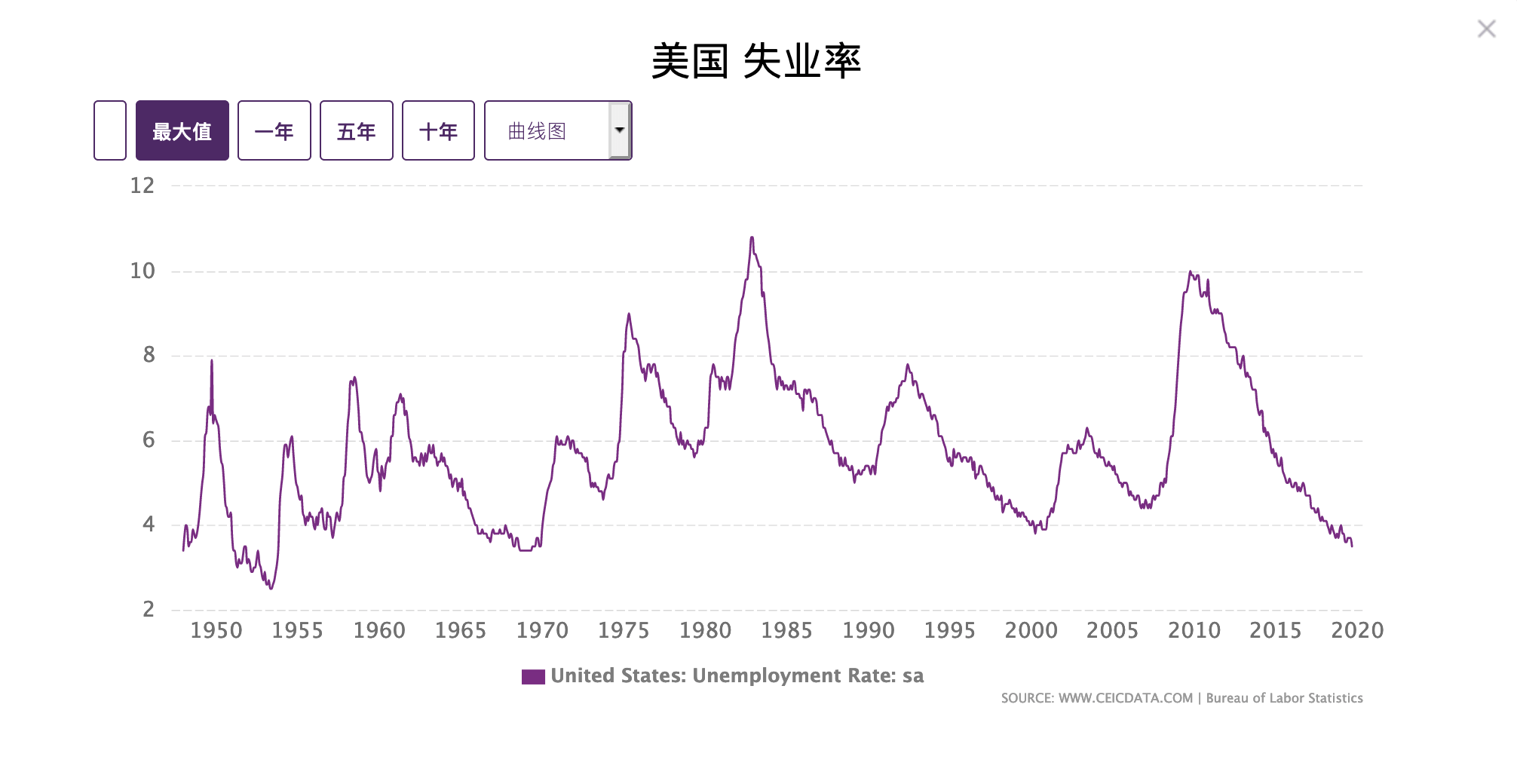

此次新冠大流行可能将美国劳动力市场拖入自“大萧条”以来最严重的危机中。金融危机和“大萧条”时期,美国的失业率最高值分别为 10% 和 25% 左右。据机构估计,疫情冲击下 4 月中旬美国失业率可能达到 16%,失业率上限将取决于经济下探程度。

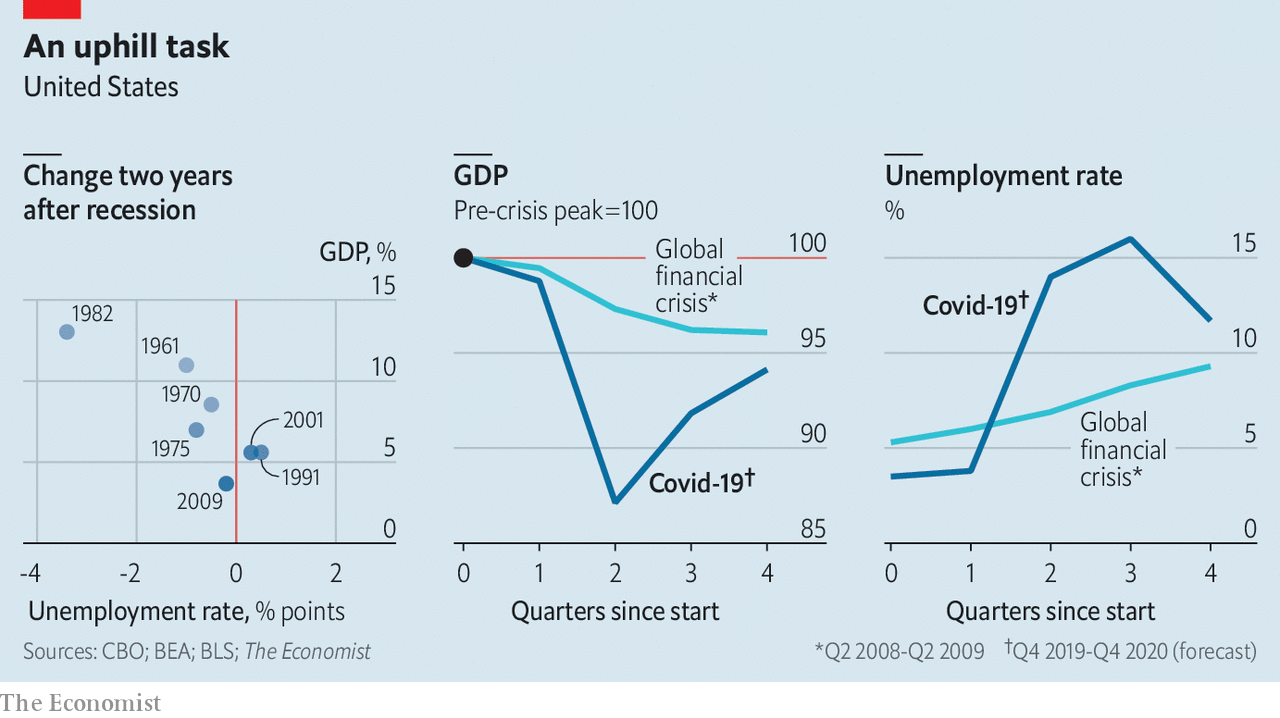

4 月 29 日公布的数据显示,美国今年第一季度 GDP 环比下滑 1.2%,美国国会预算委员会(CBO)预计第二季度 GDP 将环比下滑 12%,虽然第三季度可能反弹 5.4%,但该机构预计的 2021 年年化增长率—— 2.8% 和疫情发生前的增长速度差不多。

文章认为,如果将过去的经济产出和就业之间的关系作参考,那年化 2.8% 增长率只够将 2021 年底的失业率降至 9.5%。这意味着从现在开始的 20 个月内,美国的失业率将接近金融危机时期的失业率峰值。如果此后经济增长率一直维持在 2.8%,那美国失业率直到 2026 年才能回到疫情前的水平(注:4% 以下)。

过去危机后的经济恢复常常显现“V 型”反弹,但这并不一定总会发生。美联储大胆的“救市”举措令人印象深刻,但财政政策略显疲软,基准利率接近零也将限制美联储进一步发挥的空间。此外,疫情发生前美国家庭和企业的债务就已经很高了,随着经济下滑,债务进一步增加,一旦疫情得到控制经济开始恢复,高债务将减少新增支出的规模。

文章认为,即使是乐观估计,美国失业者的未来也显得很暗淡。假设美国的失业率能够按照 1933-37 期间的速度下降,回到疫情前的失业率水平也要花 5 年;如果按照 2007-09 年金融危机后的表现看,失业率完全恢复要花 20 年。

文章最后认为,如果没有巨大的好运和政府大量的努力,美国失业率可能再迎一个“失去的十年”,甚至“失去的二十年”。

Why the unemployed in America could face a lost decade

Free exchange

Why the unemployed in America could face a lost decade

Even under the rosiest of assumptions, a labour-market crisis is looming

Finance and economics

May 2nd 2020 edition

May 2nd 2020

THE FIGURES are staggering, even to those hardened by the experience of the global financial crisis. Disney will furlough 100,000 of its hotel and theme-park workers. Uber may slash its staff by a fifth. Fully 26m new claims for unemployment insurance have been filed in America since late March. By April 18th more than a tenth of participants in the labour force were receiving unemployment benefits, the highest rate on record. In March alone American firms shed more than 700,000 jobs, on net. Another 2m may have gone in April, a drop rivalling the record decline in employment that occurred in 1945, as America’s armed forces demobilised. Covid-19 has spread large-scale economic disruption around the world. It is increasingly clear that the pandemic confronts America with a labour-market crisis not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

How severe will the crisis be? America’s unemployment rate rose to around 10% after the global financial crisis and to 25% during the Depression. Recent forecasts, though beset by uncertainty, put the probable peak rate in 2020 somewhere between those figures. Modelling based on recent filings for benefits suggests that the unemployment rate in mid-April may have been around 16%, according to Ernie Tedeschi of Evercore ISI, a consultancy. An analysis of the macroeconomic effects of the coronavirus published on April 24th by America’s Congressional Budget Office (CBO) paints a similar, sobering picture. The CBO reckons that unemployment will rise to 14% in the second quarter of this year, and peak in the third quarter at around 16%. The rate would be even higher, but for the 8m workers it assumes will become discouraged and leave the workforce (in order to count as unemployed, people must participate in the labour market by actively seeking work). Some places and groups will fare worse than others. During the financial crisis, peak unemployment rates across states ranged from just over 4% to nearly 15%. The peak rate for black Americans, at 16.8%, was nearly twice that for whites.

The heights that unemployment reaches will depend on the depths that economic activity plumbs. There is no question that the drop in output through the first half of 2020 will be staggering. Figures published on April 29th showed that GDP fell by 1.2% in the first quarter, compared with the final quarter of 2019 (an annualised rate of -4.8%). The CBO projects that output will fall by about 12% between the first quarter and the second, or an annualised pace of roughly -40% (see chart, middle panel). But the economic and social pain of unemployment rests largely on how persistent the weakness in the labour market proves to be, which in turn depends on the pace of the economic recovery. The CBO, like many forecasters, expects America’s economy to begin growing again in the second half of the year, as restrictive measures are relaxed. They forecast, perhaps optimistically, a robust rate of growth in the third quarter of 5.4% (an annualised rate of 23.5%). A fast initial rebound might well materialise as sectors shut down by pandemic-fighting measures begin to re-open. But growth is expected to moderate thereafter to an annual rate of 2.8% in 2021, in line with America’s recent pre-pandemic performance. If the past relationship between output and job growth is a guide, such a rate will be sufficient only to reduce unemployment to 9.5% by the year’s end. In other words, some 20 months from now, unemployment may still be close to the peak reached in the aftermath of the financial crisis. If GDP growth continued at 2.8% thereafter, America would regain its pre-pandemic unemployment rate only in 2026.

As dire as the CBO’s projections are, it is difficult to see how the economy could do better. The forecast drop in the unemployment rate from the third quarter to the fourth, of 4.3 percentage points, would, if realised, easily be the fastest ever three-month decline. It would achieve in three months what took a year during the early 1940s, when America mobilised for war. In the absence of a miracle treatment or early vaccine, it is the very best America can hope for. Far easier to imagine are ways in which the forecast disappoints. New outbreaks or restrictions on activity could push output lower and delay a turnaround in the jobs market. Though economic recoveries from the 1950s to the 1980s were often V-shaped, recent business cycles have proven more lopsided. Dramatic declines in output and employment have not been followed by correspondingly steep rebounds.

Deep trouble

Many of the factors implicated in this change in recovery patterns are likely to apply as the pandemic recedes. Easing could prove insufficient. Though America’s spending on stimulus has been impressive so far, there are some signs of fiscal fatigue. The Federal Reserve has largely succeeded in averting financial-market havoc, but its ability to revive economic growth may be hampered by near-zero interest rates. Household and company debt, already high before the pandemic compared with the early post-war era, will grow more burdensome as the economy shrinks, reducing the scope for new spending once the recovery gets under way. Firms may come to view the pandemic as an opportunity to streamline production—through the use of remote-work and automating technologies, for example—potentially reducing labour demand down the road. Research by Nir Jaimovich of the University of Zurich and Henry Siu of the University of British Columbia finds that such structural shifts during downturns have contributed to the joblessness of recent recoveries.

Even in the rosiest of scenarios, the outlook for those without a job seems grim. Were unemployment to fall as quickly as it did from 1933 to 1937, a return to pre-pandemic jobless rates would still take half a decade. At the rate of improvement experienced after the financial crisis, by contrast, full recovery could take two decades. All that after the hardship of the 2010s seems nearly unthinkable. Yet without a hefty dose of good luck and an aggressive government effort, America’s unemployed face a real risk of another lost decade—or two. ■

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline"Mountain to climb"