本期经济学人杂志【美国】板块下这篇题为《How high will unemployment in America go?》的文章关注的是新冠疫情下的美国失业率情况,文章认为金融危机是比大萧条更好的参考点,但此次新冠病毒大流行对美国失业率的影响与以往的危机不完全相同。

2005 年 8 月,美国路易斯安那州的失业率达到历史最低值 5.4%,但随后的卡特里娜飓风对一些企业造成了严重影响,一个月内路易斯安那州的失业率就翻倍了。目前美国从整体来看也面临着类似的冲击,新冠疫情下,美国的失业率即将从五年来的最低点快速上升。

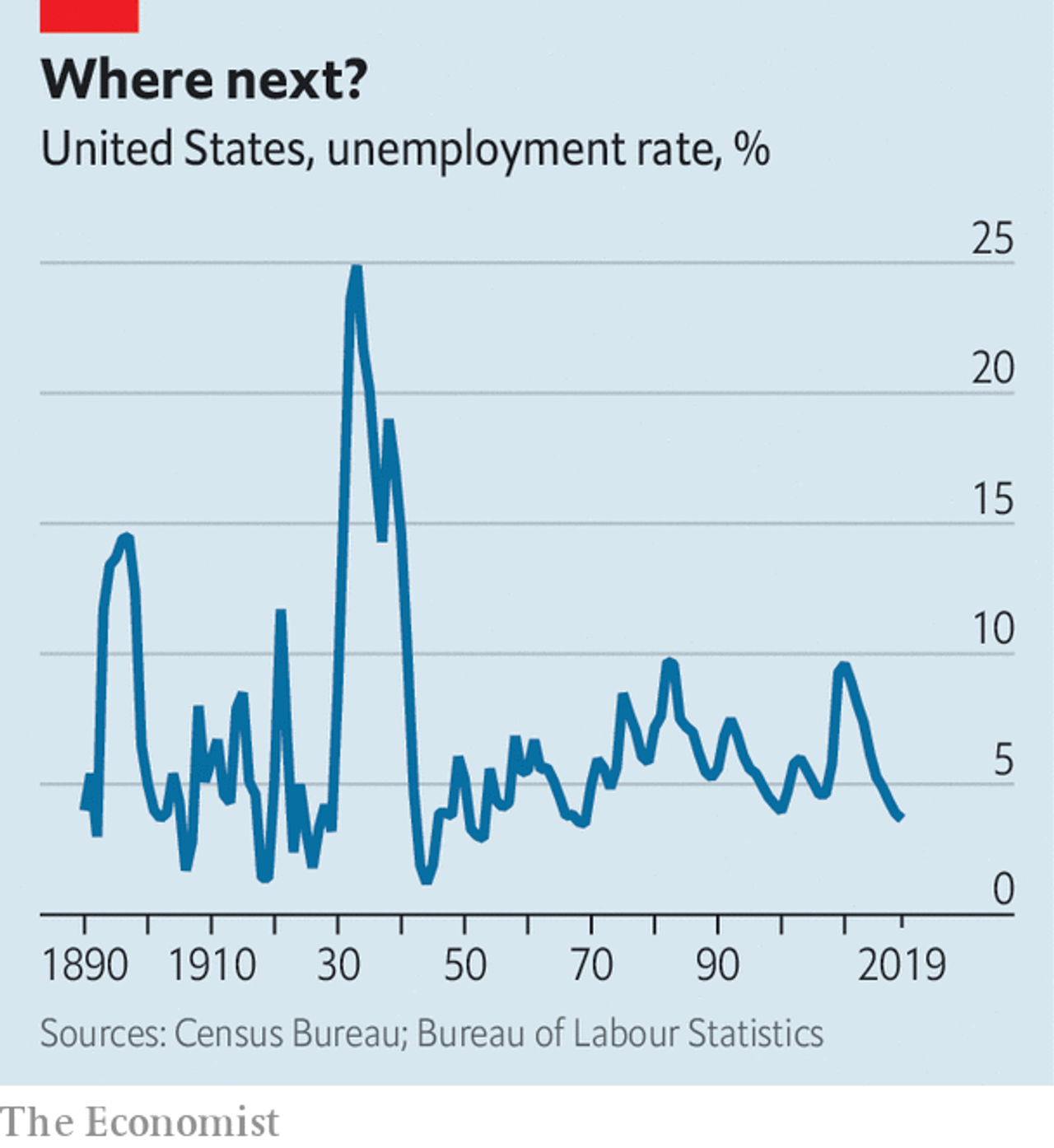

GDP 增长率和失业率两者间一般呈反向变动。大萧条期间美国的失业率曾达到历史最高值——约 25%。受疫情影响,预计今年第二季度美国 GDP 同比下降 10%,根据经验数据推测美国当季的失业率将高达约 9%,几乎达到了 2007-09 年金融危机期间美国的失业率峰值。

但文章认为此次新冠大流行对就业市场的影响与过去的经济衰退不完全一样。

- 劳动力需求可能低于往常。限制出行等疫情防治措施加大了人们找工作的难度,其中首次求职的年轻人尤其困难;即使企业没有临时裁员,疫情期间企业招聘暂停也将推高失业率。

- 疫情对劳动力市场的影响将主要集中在劳动力密集型行业,特别是休闲和服务业。

穆迪分析师预计美国失业率可能高于 20%。圣路易斯储备银行的报告比较悲观,认为今年第二季度会有接近 5,000 万的美国人失去工作,这足以将失业率推高至 30% 以上。

但文章认为美国实际的失业率可能不会那么高,如果疫情一旦结束失业率能够快速降下来,那短期内失业率高一点问题不大。路易斯安那州在熬过 2005 年末最艰难的几个月后,该州的失业率快速下降。

高盛研究人员认为,美国的失业率到 2023 年才会重回 4% 下方。新冠疫情下的停工潮可能是暂时的,但它对经济的影响将持续很久。

Trough to peak: How high will unemployment in America go?

Trough to peak

How high will unemployment in America go?

The financial crisis looks a better reference point than the Depression

United States

Apr 1st 2020 edition

Apr 1st 2020

Editor’s note: The Economist is making some of its most important coverage of the covid-19 pandemic freely available to readers of The Economist Today, our daily newsletter. To receive it, register here. For more coverage, see our coronavirus hub

IN AUGUST 2005 the unemployment rate in Louisiana was 5.4%, close to its all-time low. Then Hurricane Katrina hit. The storm destroyed some firms, while others were forced to close permanently. Within a month, Louisiana’s unemployment rate had more than doubled.

Now America as a whole faces a similar shock. From a five-decade low, early data suggest unemployment is shooting upwards, as the onrushing coronavirus pandemic forces the economy to shut down. Millions of Americans are filing for financial assistance. The jobs report for March, published shortly after The Economist went to press, is a flavour of what is to come—though because the survey focused on early to mid-March, before the lockdowns really got going, it is likely to give a misleadingly rosy view of the true situation. How bad could the labour market get?

GDP growth and the unemployment rate tend to move in opposite directions. Unemployment hit an all-time high of around 25% during the Great Depression (see chart). The coronavirus-induced shutdowns are expected to lead to a year-on-year GDP decline of about 10% in the second quarter of this year. Such a steep fall in economic output implies an unemployment rate of about 9% in that quarter, based on past relationships, which would be roughly in line with the peak reached during the financial crisis of 2007-09.

But the coronavirus epidemic is not like past recessions. For one thing, hiring could be even lower than is typical. Delivery firms notwithstanding, surveys suggest that firms’ hiring intentions are as low or lower than they were in 2008. And applying for a job is especially difficult with cities in lockdown. Even without a single virus-induced layoff, hiring freezes would lead to sharply rising unemployment. For instance, young people entering the labour market for the first time now would struggle to find work.

The decline in GDP associated with the lockdowns is also particularly concentrated in labour-intensive industries such as leisure and hospitality. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics, a research firm, calculates that more than 30m American jobs are highly vulnerable to closures associated with covid-19. Were they all to disappear, unemployment would probably rise above 20%. Research published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis is even gloomier. It suggests that close to 50m Americans could lose their jobs in the second quarter of this year—enough to push the unemployment rate above 30%.

The numbers will probably not get that bad. In part that is a matter of statistical definitions. To be officially classified as unemployed, jobless folk need to be “actively seeking work”—which is rather difficult in the current circumstances. Some people could end up being counted as “economically inactive” rather than unemployed, which would hold down the official unemployment rate (a similar phenomenon occurred in Louisiana after Katrina).

America’s economic-stimulus bill will be a more genuine check on rising joblessness. The $350bn (1.6% of GDP) set aside for small firms’ costs is enough to cover the compensation of all at-risk workers for perhaps seven weeks, according to our calculations, making it less likely that bosses will let them go. Other measures in the package should support consumption, and thus demand for labour. In a report published on March 31st Goldman Sachs, a bank, argued that unemployment will peak in the third quarter of this year at nearly 15%—an estimate that is roughly in line with those of other forecasters.

A big jump in unemployment is less of a problem if it quickly falls once the lockdown ends. Louisiana offers an encouraging precedent. After a few bad months in late 2005, the state’s unemployment rate dropped almost as sharply as it had risen, falling in line with the rest of the country. Whether the economy will prove so elastic this time is another matter. Travellers and restaurant-goers will be cautious until some sort of vaccine or treatment is widely available; social-distancing rules, even if relaxed, will continue for some time. Goldman Sachs’s researchers reckon that it will take until 2023 for unemployment to fall back below 4%. The lockdowns should be temporary, but the economic consequences will feel much more permanent.■

Dig deeper:

For our latest coverage of the covid-19 pandemic, register for The Economist Today, our daily newsletter, or visit our coronavirus hub

This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline"Trough to peak"