本期经济学人杂志【经济金融】板块下这篇题为《V is for vicious: How to deal with a new sort of financial shock》的文章认为,每一次金融冲击都不一样,对新冠病毒引发的恐慌带来的金融风险各国政府和监管机构等需要快速应对。

面对令人困惑的市场,人们很自然地会参考自己过去积累的经验,对许多人来说 2007-09 年的次贷危机属于这类经验。当前的金融冲击与次贷危机有许多相似之处,如股市突然下跌、油价跌破 40 美元/桶以及美联储和其他央行紧急降息等。

但文章认为把当前的金融冲击与上次大的金融危机相比是不适宜的,区别主要体现在以下两大方面:

一、股市暴跌的严重程度不及 2007-09 年的次贷危机。当前股市从最高点下跌了 1/5,而次贷危机期间股市下跌了 59%;当前不良贷款量有限且容易识别;大约只有 15% 的非金融公司债由石油公司、航空公司和酒店发行,这些企业因为新冠肺炎疫情和“石油价格战”受到较大影响。此外,银行系统运转正常,银行间借款利率可控。

二、两次金融冲击的本质不一样。2007-09 年的次贷危机源于金融系统内部,而此次冲击主要是由于新冠病毒引发的健康危机造成的。

文章认为,虽然与次贷危机搞垮华尔街、引发住房贷款违约潮不同,但此次金融冲击也潜伏着两大危机,需要各国政府和监管机构共同携手快速应对。

- 企业短期资金紧张。次贷危机期间政府将资金输入银行系统,保证其流动性和刺激债券市场。但现在政府的挑战是要创造性地利用减税等方式将资金输入企业,鼓励债权人对债务人多一些宽容。

- 关注欧元区。目前欧洲央行的利率已经低于 0。虽然当前欧洲的银行较 2008 年健康许多,但相比美国的银行仍很弱。在意大利,违约的保险成本跃升,这意味着银行基金成本增加。

How to deal with a new sort of financial shock

V is for vicious

How to deal with a new sort of financial shock

The subprime crisis is not a good guide to markets today

Leaders

Mar 12th 2020

WHEN FACED with a bewildering shock it is natural to turn to your own experience. As covid-19 rages, investors and officials are scrambling to make sense of the violent moves in financial markets over the past two weeks. For many the obvious reference is the crisis of 2007-09. There are indeed some similarities. Stockmarkets have plunged. The oil price has tumbled below $40 a barrel. There has been a flurry of emergency interest-rate cuts by the Federal Reserve and other central banks. Traders are on a war footing—with a rising number working from their kitchen tables. Still, the comparison with the last big crisis is misplaced. It also obscures two real financial dangers that the pandemic has inflamed.

The severity of the shock so far does not compare with 2007-09. Stockmarkets have fallen by a fifth from their peak, compared with a 59% drop in the mortgage crisis. The amount of toxic debt is limited and easy to identify. Some 15% of non-financial corporate bonds were issued by oil firms or others hit hard by the virus, such as airlines and hotels. The banking system, stuffed with capital, has yet to seize up; interbank lending rates are under control. When investors panic about the end of civilisation they rush into the dollar, the reserve currency. That has not yet happened.

The nature of the shock is different, too. The 2007-09 crisis came from within the financial system, whereas the virus is primarily a health emergency. Markets are usually spooked when there is uncertainty about the outlook six or 12 months out, even when things seem calm at the time—think of asset prices dropping in early 2008, long before most subprime mortgage borrowers defaulted. Today, the time horizon is inverted: it is unclear what will happen in the next few weeks, but fairly certain that within six months the threat will have abated.

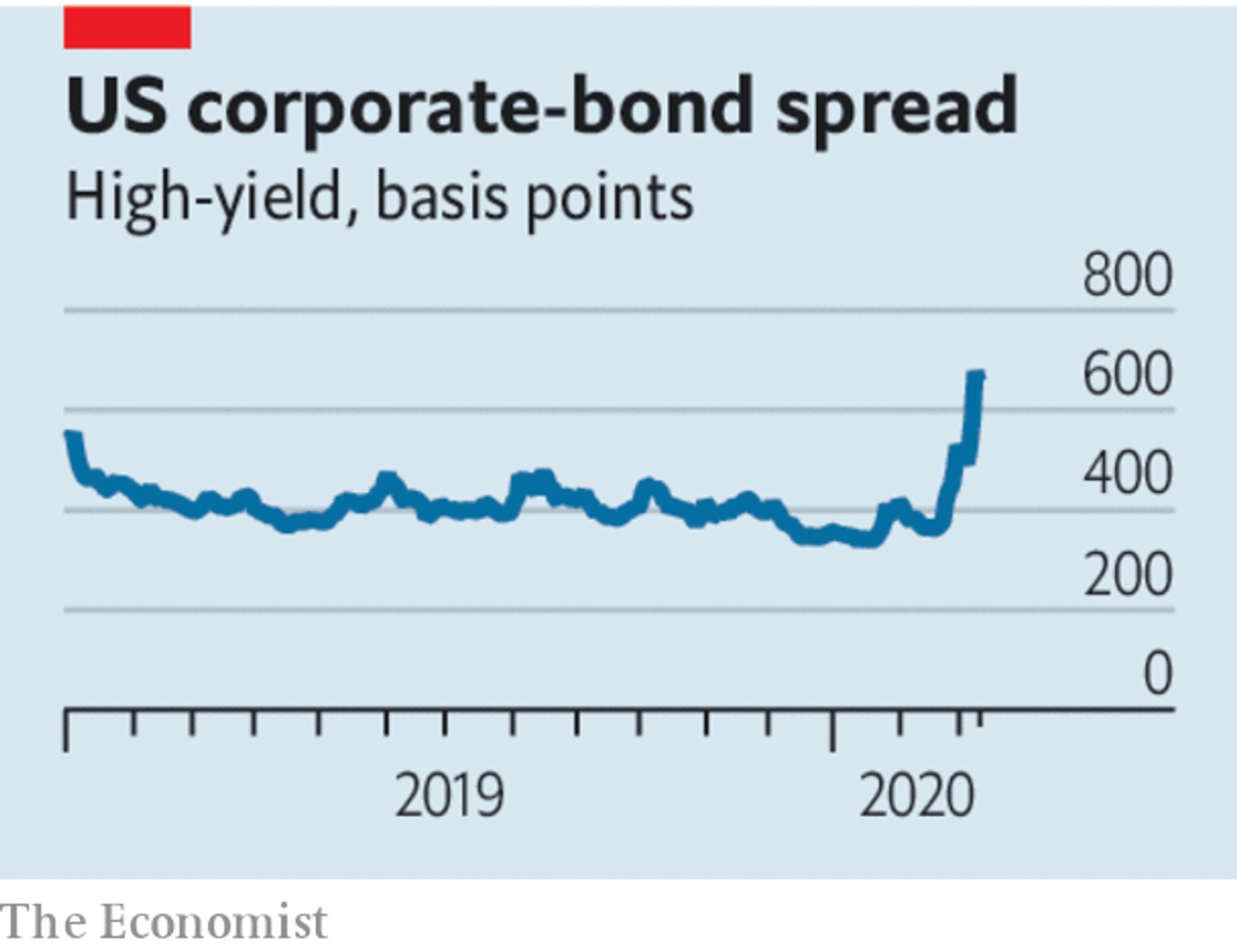

Instead of tottering Wall Street banks or defaults on Florida condos, two other risks loom. The first is a temporary cash crunch at a very broad range of companies around the world as quarantines force them to shut offices and factories. A crude “stress test” based on listed companies suggests that 10-15% of firms might face liquidity problems. Corporate-bond markets, which demand precise contractual terms and regular payments, are not good at bridging this kind of short but precarious gap.

In 2007-09 the authorities funnelled cash to the financial system by injecting capital into banks, guaranteeing their liabilities and stimulating bond markets. This time the challenge is to get cash to companies. This is easy in China, where most banks are state-controlled and do as they are told. Credit there grew by 11% in February compared with the previous year. In the West, where banks are privately run, it will take enlightened managers, rule tweaks and jawboning from regulators to encourage lenders to show clients forbearance. Governments need to be creative about using tax breaks and other giveaways to get cash to hamstrung firms. While America dithered, Britain set a good example in this week’s budget.

The second area to watch is the euro zone. It is barely growing, if at all. Central-bank interest rates are already below zero. Its banks are healthier than they were in 2008 but still weak compared with their American cousins. Judged by the cost of insuring against default, there are already jitters in Italy, the one big economy where banks’ funding costs have jumped. As we went to press, the European Central Bank was meeting to discuss its virus response. The danger is that it, national governments and regulators fail to work together.

Every financial shock is different. In 1930 central banks let banks fail. In 2007 few people had heard of the subprime mortgages that were about to blow up. This financial shock does not yet belong in that company. But the virus scare of 2020 does create financial risks that need to be treated—fast.■

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition under the headline"V is for vicious"